SVC professor’s internship program aims to help continue gradual cleanup of local waterways

SVC professor’s internship program aims to help continue gradual cleanup of local waterways

-

Side Navigation

- Saint Vincent College to partner with West Penn Power Sustainable Energy Fund to bring solar-powered charging station to campus

- Verostko Center announces new exhibition featuring members of Associated Artists of Pittsburgh

- Saint Vincent College to celebrate Life in Christ Week

- December SVC grad commissioned as army officer

- SVC APB wins regional award for record fifth year in a row

- Student spotlight: Bridgette Gorg

- The European Journal of Physics accepts latest work by SVC emeritus professor

- SVC theology professor to present talk on women in the Bible

- SVC biology professor leads study of connection between alcohol and nicotine addictions

- New Bachelor of Science in “Aviation Management – Professional Pilot” takes flight at Saint Vincent College

- SVC students’ documentary “Don’t Count Us Out” wins Gold Viddy Award

- Somerset Trust donates to Saint Vincent Small Business Development Center

- National top-10 ranking for Saint Vincent’s M.S. in Criminology program

- Fall 2023 Dean's List

- SVC’s Monastery Run Improvement Project significantly improves water quality along Four Mile Run

- Saint Vincent College theology professor’s book takes a deeper look at Laudato Si’

- Alumni spotlight: Charles Farley inducted into a pair of high school coaching halls of fame

- SVC Announces 2024 Wimmer Scholarship Award recipients

- Alumni spotlight: At work and at home, Aubrey Marquis is driven by philanthropy

- SVC extends deadline for financial aid filing, Bearcat Advantage Program to May 1

- The SVC Players to present “The Sound of Music” Feb. 22-25

- Alumni Spotlight: Cameron Klos

- Pittsburgh native Dr. Ruth Langer to speak at SVC’s annual Rabbi Jason Edelstein Lecture for Catholic-Jewish Dialogue

- SVC alumnus who authored “Masters of the Air” explains backstory of his book and the Apple TV+ series

- Four students participate in mock Supreme Court argument

- Alumni spotlight: Former FBI analyst Paul Hodos discusses “Steel City Mafia,” his second nonfiction book

- Alumni Spotlight: Anne Darla Pamphile

- The Latrobe/Greensburg Homeschool Science Fair returns

- Student spotlight: Alissa Minerd

- SVC panel discussion with Federated Hermes emphasizes data science’s role in asset management

- Alumni Spotlight: Brianna Baum

- Student Spotlight: Maci Rogers

- U.S. News & World Report ranks SVC’s MS in Management: Operational Excellence a top online master’s in business program for seventh straight year

- SVC professor’s internship program aims to help continue gradual cleanup of local waterways

- SVC Concert Series to present traditional Chinese woodwind program March 15

- Education honor society welcomes new members

- SVC men’s hockey team heads to D3 national tournament after winning league championship

- Student spotlight: Julie Zhu

- Fred Rogers Institute to host Community Open House

- Expert to speak at Saint Vincent about the ethics of keeping partly rehabilitated birds in captivity

- 2024 Challenge Program registration now open

- SVC math professor enjoys “reunion” in Italy at program for commutative algebra research

- SVC physics department will conduct solar eclipse program and planetarium shows

- Student spotlight: Luca Rosato

- Alumni Spotlight: Meg Matich awarded National Endowment for the Arts Literary Translation Fellowship

- SVC holds quantum computing workshop for local STEM teachers and students

- SVC to host women in business panel discussion

- SVC hosts successful Heart of Teaching conference

- Student spotlight: Austin Slye

- SVC physics researchers search for possible effects of solar eclipse on cosmic showers

- Saint Vincent to host annual Summer Theatre gala on April 12

- Saint Vincent College to host eclipse viewing event April 8

- Saint Vincent College earns silver, bronze honors in annual Educational Advertising Awards

- Student spotlight: J’Shawn Taylor

- SVC to host presentation about Catholic Rural Ministry

- Student spotlight: Jacqueline Moon

- SVC to host 2024 senior art showcase

- Saint Vincent College announces updated plans for new athletic center

- Antique coverlet exhibit will open April 17 at Saint Vincent College’s McCarl Gallery

- SVC education department to host educator and author Dr. Todd Whitaker

- SVC welcomes Sr. Gabriele Vasiliauskaité as inaugural Stephans Family Visiting Benedictine Professor

- Saint Vincent College announces Susan Baker Shipley as Spring 2024 Commencement speaker

- News

- Mr. Safin’s “From the Heart” captures filmmaking award

- Saint Vincent College extends new student commitment deadline to June 1

- SVC to host 21st annual Academic Conference

- SVC reveals finalists for 50th annual President’s Award

- SVC student will study in Wales as part of Fulbright Summer Institute program

- Saint Vincent College to build Rhodora and John Donahue Hall to house nursing program

- SVC Concert Series continues with “(S)Heroes” from the IonSound Project

- Saint Vincent College students, faculty recognized at 2024 Spring Honors Convocation

- Olivia Persin is named 2024 SVC President’s Award winner

- Dr. Sara Lindey receives Boniface Wimmer Faculty Award

- Dr. Lucas Briola receives Quentin Schaut Faculty Award

- Alumni spotlight: Chris Golias

- Attorney Daniel Lynch, C’89, delivers 2024 Spring Honors Convocation address

- Hiring event set for 2024 Steelers training camp at SVC

- SVC communication students query Bishop Zubik during mock press conference

- Auditor General Timothy DeFoor makes recruiting pitch to students during Saint Vincent College visit

- SVC students Cameron Walker and Lauren Brennan honored at Education Department’s annual senior send-off picnic

- ‘The Marvelous Wonderettes’ kicks off Saint Vincent Summer Theatre’s 2024 season

- SVC professor receives $200,000 grant from National Science Foundation to study water desalination

- Seven SVC students participate in mock Supreme Court arguments

- Saint Vincent College students win for best statistical analysis at DataFest competition

- Saint Vincent College holds 178th Spring Commencement

- Spring 2024 commencement address by Ms. Susan Baker Shipley

- SVC engineering students cap Spring 2024 semester by presenting wind tunnel projects

- SVC graduate Dominic Oto commissioned as Army officer

- SVC alumna Elizabeth Elin wins 2024 Clark Award for religious studies and theology

- SVC is recognized as a College of Distinction

- SVC’s Dr. Tim Kelly quoted by The Associated Press

- 2024 SVC Challenge Program registration ends May 31

- SVC Birding Team participates in World Series of Birding

- Alumni spotlight: Matt Bertone

- Trip to Portugal provided SVC students and alumni with global perspective

- Saint Vincent Summer Theatre offers special trolley trip for “Unnecessary Farce”

- SVC McKenna School dean and adjunct professor honored by Boy Scouts with Trailblazer Awards

- Digital art pioneer Roman Verostko, 94, dies

- Saint Vincent College ranked among top 10 Pennsylvania colleges in 19 degree programs

- SVC President Fr. Paul Taylor listed among 2024 Trailblazers in Higher Education

- Rev. Dr. Clarence E. Wright named inaugural Fred Rogers Fellow

- Dr. Mary Regina Boland quoted by Catholic News Agency

- Student spotlight: Natalie Homison

- Dr. Mary Beth Yount chosen to fill SVC’s Irene S. Taylor Endowed Chair for Catholic and Family Studies

- 35th annual Saint Vincent College Week brings 41 Crossroads Foundation scholars to campus

LATROBE, PA — For nearly 30 years, the man-made wetlands on the Saint Vincent Archabbey property have helped improve local streams by naturally treating the water that drains from abandoned mines. Yet, other pollutants still lurk in the waterways.

Are local watersheds cleaner than they were three decades years ago? Yes, but …

“It depends on where you’re looking and what you’re looking for,” said Dr. Peter Smyntek, associate professor of Environmental Science at Saint Vincent College (SVC). “The biggest, most obvious things, such as mine drainage, are getting better. But we’re also learning about what else we need to look for. When we understand more about what’s happening in our local streams, we can focus on treatment priorities.”

That is why each year Smyntek takes on a small group of student interns to monitor and analyze the interaction of mine drainage and sewage in local watersheds. Since 2017, Smyntek and his students have been collecting water and sediment samples from local streams, including Fourmile Run near the SVC campus, Brush Creek in Irwin, and Jack’s Run and Sewickley Creek in Greensburg.

The man-made wetlands of the Monastery Run Improvement Project adjacent to the SVC campus were developed in 1997 and 1998. The 20 acres of wetlands treat water that drains from abandoned mines and flows into Fourmile Run, Monastery Run and Loyalhanna Creek.

“The wetlands do a good job of removing a lot of the mine drainage,” Smyntek said. “But the idea here is there also is other nutrient pollution [from sources such as sewage and fertilizer runoff] that’s kind of being hidden by the mine drainage.”

Iron from mine drainage that seeps into streams gives the streambeds an orange sheen. When these pollutants stick to the sediment in streambeds, the levels of phosphorus, a key nutrient in the water, go down. As more mine drainage is remediated, the phosphorus levels in the stream that the mine drainage was controlling may begin to increase. This may cause harmful algal blooms in downstream aquatic systems, which lower oxygen concentrations and potentially release toxins that can affect both people and aquatic organisms.

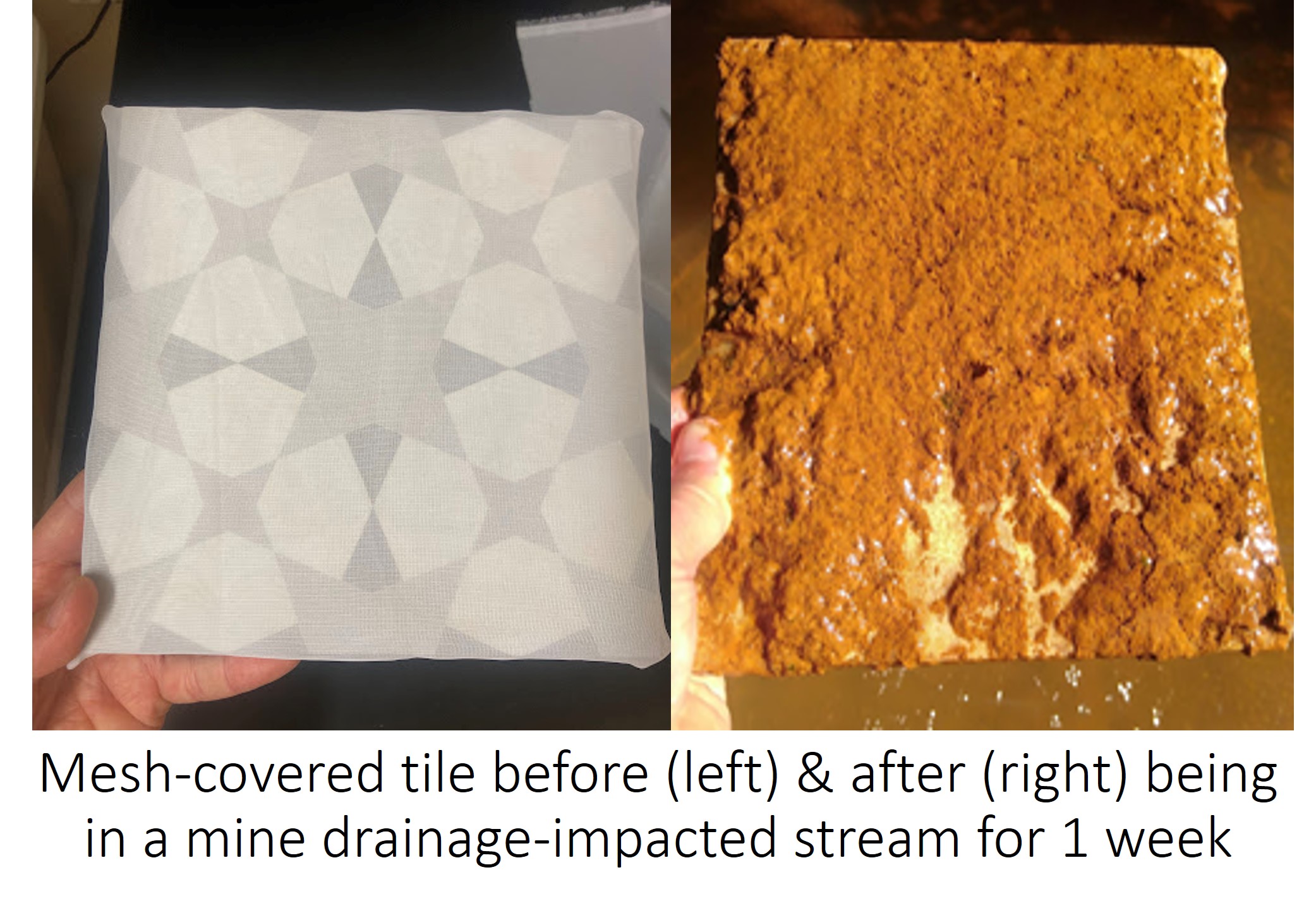

“When you sample the water, you don’t normally sample the sediment,” Smyntek said. A few years ago, he and his interns began placing mesh-covered tiles on streambeds to collect polluted sediment for analysis.

Groups such as the Sewickley Creek Watershed Association, the Loyalhanna Creek Watershed Association, and the Westmoreland Conservation District may use Smyntek’s data when applying for grants to fund cleanup efforts. Earlier this month, he shared his data with the Municipal Authority of Westmoreland County officials who monitor water quality for local drinking water treatment facilities.

“The big [problems] are getting better,” Smyntek said. “If you were to drink stream water or eat a fish from it, you’re safer now than you were 10 years ago. We’re learning more about what else we need to do and what we need to consider threats that we weren’t aware of before.”

For some students, Smyntek’s internship program is their first contact with hands-on field work. They gain valuable research experience and provide a tangible service to the local community. “It’s a chance for them to literally get their feet wet,” Smyntek said with a grin.

John Pawlak, C 25, an environmental science major from North Huntingdon, was part of the internship group last summer. “Going into the internship, confidence was not something that was easy for me to find,” Pawlak wrote last December in his internship reflection. “This changed for the better as a direct result of the work [in which] I participated.”

For more information, contact peter.smyntek@stvincent.edu.

PHOTO 1: SVC student John Pawlak measures the water flow rate in Brush Creek in Irwin.

PHOTO 2: A mesh-covered tile before and after being in a mine drainage-impacted stream for one week.